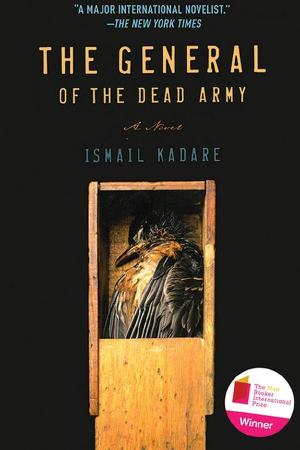

The General of the Dead Army by Ismail Kadare

Traditional war books tend to verse of heroism, glorifying the victorious side and relate how battles were fought in the name of whatever sacred ideal the protagonists believe in. Nevertheless, The General of the Dead Army by Ismail Kadare focuses not in the battlefield, but on the aftermath of war. On the book, we witness the journey of a Italian General and a priest officer, who were commissioned with the task of finding and repatriating the dead bodies of their fallen soldier who occupied Albania twenty years ago, during the World War II, to ensure they receive a proper burial.

Given that Kadare is Albanian, we might think this is another chauvinistic novel to salute the Albanian resistance movement. However, the story is told from the perspective of the former invaders. The General gloomy and administrative job leads him to travel from town to town through the intricate Albanian landscapes, following the dots marked on map where the soldiers lie. After every exhumation performed by local Albanians used as task force, the bones are disinfected, some measurements are taken, and the dental records are compared with a list of names, which are crossed off when matched. The white remaining of the soldiers are then packed in nylon sacks and thrown into a truck, after a brief religious ritual. As the General carries out his duty, he gradually starts to confront the scars left by the war, but not only the physical impact, but the psychological and spiritual consequences that have been printed on the collective memory of Albanians.

Kadare wrote the novel using a simple, yet somber tone, recurring to repetitive structures to emphasize the futility of the work charged to the General. Even though the General is the main character, and basically all the narrative revolves around him, there are interesting secondary characters that serve as a contrast with the General—most notably, the military priest. The dutiful and pragmatic general is often confronted by the more reflexive nature of the priest about topics like war, moral burden and the meaning of the task.

Throughout the novel, we can find interesting events like people at the beginning of the novel pleading for the retrieval of their missing relatives. Among the requesters, are the mother and wife of the mysterious Colonel Z., the Commander of the infamous Blue Battalion—a military punishment unit. The Colonel Z. is described initially as a a virtuous man, sensitive to “all the beautiful things in the world” by her mother; however, as the general retraces the colonel’s path, what emerges is a trail of pain, blood and devastation, revealing the brutality of his true nature.

The depiction of Albania made by Kadare turns the landscape into another hostile character that seems to conspire against the General mission. Indeed, as days pass by, the oppressive atmosphere and the mechanical repetition of the task begin to take their toll on the psychological state of the general and the priest. One particular and revealing moment comes when the general states that he “no longer see heads, but only skulls on people’s shoulders”. It is enlightening to understand to what extent work has disturbed his psyche. The General also wonders if this tasks actually gives any relief or, as the testimony found from a dead soldier, it’s nothing more than hypocrisy taking care of soldiers after death when they serve as a symbolic function. For the General, it becomes clear that his task has been stripped of any sacred aura: after a time not even the religious ritual of the buries has another meaning than a bureaucratic and tedious routine. The speech and words have lost their content, becoming hollow, reducted to just a uncomfortable performance masqueraded as a national duty.

The novel illustrates how the history and collective memory are entangled together. Although the General himself did not fight in the war, he’s a symbol of the former occupation for the Albanian villagers, who conveys a veiled hostility and passive resistance to cooperate—including the Albanian translator assigned to the General. This tension is specially accentuated every time the General or priest try to reconstruct the path of Colonel Z., forcing the reader to confront the symbol of brutality left behind for one side, against the ideological narrative reconstruction of duty and heroism.

Though the enigmatic Colonel Z. is long dead, his shadowy figure haunts from the past. He represents a lasting stain of violence and the inescapability of guilt proving that some things cannot be undone or forgotten, and sometimes there is no forgiveness in any tomorrow. This is especially evident in episodes describing how Colonel Z. executed deserters from his own platoon—soldiers who had chosen to abandon the war and live as servants among the Albanian villagers—and in the ruthless punishments he inflicted on the local population every time he visited them. The revelation of the fate of Colonel Z. is the most tense and emotionally charged moments in the novel.

By the end of the novel, the once proud General initially committed to his duty with a sense of national pride and moral obligation can no longer ignore the banality of his mission. The General of the Dead Army comes to conclude that some wounds remain open, beyond the time, but keeping the weight of history. The past, as Kadare suggest, sometimes cannot be fixed or reconciled and there is no space for forgiveness. In war, it becomes nearly impossible to separate the tragic from the grotesque, the heroic from the regrettable. War may end, but its shadow lingers in memory.